Blame it on Hollywood or mass media representation, but there is a popular view of Eastern Europe as a gray uniform mass, a type of international backwater housing perennial “bad guys” in the ongoing East vs. West narrative since the fall of the Berlin Wall.

That vision does little to help understand how Poland’s GDP growth in 2024, for example, is projected to be double of European Union’s, or why we’re seeing a disproportionate number of Eastern European engineers at leading startups in Silicon Valley, including OpenAI. These Western stereotypes also do little to explain why communities in Poland and other parts of Eastern Europe have come to Ukraine’s aid right away and taken the Russian government’s threat to reinstate its empire seriously from the very start.

To understand the present and the future of Eastern Europe, we need to get comfortable with its past.

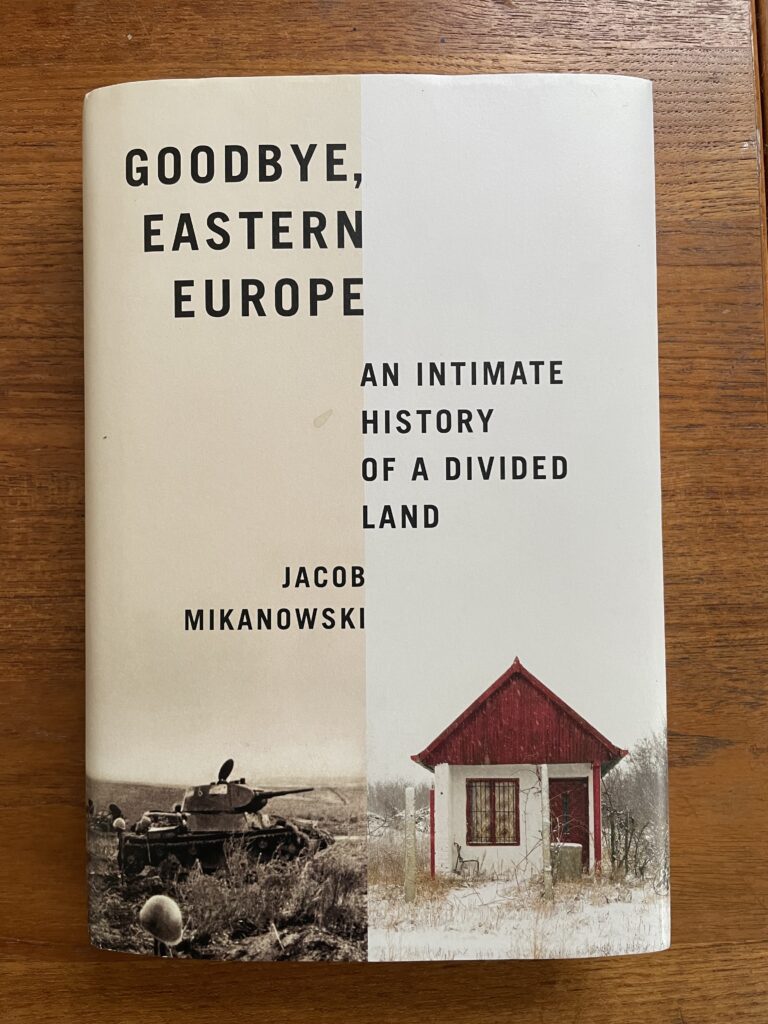

Jacob Mikanowski’s recent book Goodbye, Eastern Europe: An Intimate History of a Divided Land, does just that, providing a sweeping overview of the region and evolution of its nations, power struggles and beliefs.

His work is also a timely reminder of what happens when the freedom to practice those beliefs and exercise political independence are suppressed. This year will have a record number of elections in history, with more than 60 countries going to the polls. At a time when accusations of antisemitism and fascism are accelerating around the world, Mikanowski’s narrative is a powerful reminder of where that type of political environment could lead and what we stand to lose.

Goodbye, Eastern Europe offers one of the most vivid accounts of historical illusions, delusions and possibilities–including multicultural diversity, madness of its rulers and highly skilled, resilient human capital–that it has had to offer the world in the past centuries as well as in its recent past.

Notably, what makes the book so effective is that it’s not just a dry account of the region’s lands and larger-than-life rulers. Interwoven into the book’s narrative is the author’s personal family history.

Mikanowski is a son of first-generation Polish immigrants who settled reluctantly in the United States in the 1980s. While his parents grew up a few blocks from each other in Warsaw, Poland, they only met in America.

“In early 1981, my mom was visiting her aunt on a six week tourist visa, my dad was doing a semester abroad,” Mikanowski recalls. “They got trapped [in the U.S.] by the declaration of martial law in Poland.”

Growing up in a Polish-speaking household in the U.S. got Mikanowski interested in the region, which he eventually studied in college, later pursuing academic research and then working on this book for a more general audience. He spent about six months traveling around the region for his project.

Echoes of a Multicultural Past

While many may associate Eastern Europe with state-fueled antisemitism, things weren’t always this way.

Mikanowski’s description of a region now known as “Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, much of Ukraine and parts of Latvia” in the 14th century may surprise many readers.

“This vast realm was underdeveloped and undersettled. Best of all, it was a tolerant place, especially in matters of religion,” he writes. “In this joint monarchy (later renamed the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth), Catholic, Protestant and Orthodox believers could all rub shoulders. Muslims and Jews were also welcome, the former serving as mounted soldiers, and the latter working for wealthy noblemen as merchants and tradesmen.”

Imagine if these types of historical narratives were more widely taught around the world, so that everyone grew up learning about cross-faith coexistence, not as some kind of liberal utopia, but as something we have already successfully achieved as humanity in the past.

“Christians and Muslims relied on the same folk medicines and raided each other’s traditions for cures,” Mikanowski’s retelling of Eastern European history reminds us. “Muslims kissed Christian icons and had their children receive Christian baptisms; Christians on their sickbeds invited Muslim dervishes, or members of Muslim spiritual brotherhoods, to read the Koran over them.”

This is not to say that the history of Eastern Europe was all rainbows and unicorns. Mikanowski’s descriptions of the ghettos and the sacrifices some of his Jewish ancestors made to secure work or try to stay alive were harrowing–and, again, timely reminders of what is at stake when antisemitism and fascism rear their heads and neighbors, even children, start turning in their neighbors to authorities.

Imperialist Ghosts

Reading through the chapters on the rise of Stalinism, it’s hard not to see parallels with Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine.

You’d think the threats and delusions of violent rulers with imperial ambitions would be left in history books centuries ago, and yet we’re still grappling with deluded rulers who see themselves as continuing the legacy of the 18th century tsars.

“There’s a cynicism to the Russian arguments, it’s fascinating to see official Russian justifications they draw on and how far back they go, to justify what they’re doing in the present because they leap past the entire Soviet era back to Catherine the Great, Peter the Great, which is kind of a stretch in the modern world,” Mikanowski says.

Regardless of the Russian government’s rhetoric, the impact of war in Ukraine on the relationships between its neighbors hasn’t been easy to predict for anyone, given the messy regional history.

“There’s a lot of historical tension and bad blood between Poland and Russia, Poland and Ukraine, because of the events of World War II especially, the memory of Ukrainian Polish civil war that is very well remembered in Poland is pretty bloody,” Mikanowski says, noting the war in Ukraine has led to a reorganization of existing alliances. “In two years, there are still some economic issues, but Poland is closer to Ukraine and Hungary is drawing closer to Serbia.”

Human Capital

While there isn’t a long history of entrepreneurship in Eastern Europe, there is a longer track record of solid education and technical skills especially in math and sciences going back to the Soviet era.

“The socialist state wasn’t great economically, but economic development did a good job of building human capital,” Mikanowski notes. “You actually had, on one hand, very low development coming out of socialism in the 90s, but high human capital.”

In combination with low wages, these marketable skills and talents fueled the first immigration wave to Silicon Valley, attracting Eastern European engineers and entrepreneurs to the U.S. and Western Europe.

As Mikanowski’s narrative shows in the early part of the book, the region’s relative isolation and persistent illiteracy created enclaves where mystical or heretical beliefs thrived, creating interesting amalgamations of beliefs.

For example, here’s the story of Genesis, the Eastern European heretics’ version:

“From Estonia to Macedonia, people knew the story of the earth-diver–sometimes a man, sometimes a bird, and sometimes the Devil himself–who at the start of creation dove down into the primordial sea to bring up a speck of dirt from which to conjure the earth as a whole. But at the beginning of time, in some parts of Bulgaria, it was said, there was no sea and no dirt. The earth was like a ball of dough. God kneaded it and formed it into the shape of the land and the heavens in the way an old woman stretches puff pastry to make banitsa, a stuffed yogurt and cheese pie. The Hutsuls of the Carpathian Mountains in Ukraine expanded on this dairy theme, claiming that at the beginning of time the world was made not of water or dough or waste but of rich, thick sour cream.”

While you may not be ready to buy the Sour Cream Genesis story just yet, for Westerners or outsiders the book offers a great brief overview of Eastern European history or inspiration to hop on a plane to discover the region for themselves.

For anyone from the region, it may give a glimpse of a shared past.

“The idea of Eastern Europe is kind of disappearing, people don’t want to be associated with it,” Mikanowski told Icebreaker, noting that some Baltic countries are rebranding themselves as Scandinavian.

He says the region doesn’t have to define itself in terms of anti-Russian aggression or pro-EU globalization values.

“There was a kind of cultural accomplishment and a set of values that even in spite of themselves, looking across history and European civilization, there was a capacity for living together, living with differences, living side by side–that’s worth commemorating and remembering and maybe going back to something,” he says.

Add comment